The Creator Economy will look like the Music Business.

Historically, to learn, build, or distribute ideas, you needed permission from institutions such as universities, banks, or the media… That time is over. The internet gave birth to a new phenomenon: The creator, an individual who scales without permission.

In this post-permission world, millions of creators are chasing the internet dream in the hope of finding virality, just like millions of diggers used to chase the American dream in the hope of finding gold. This digital gold rush follows the same pattern as its predecessors: while some creators are making large fortunes, becoming a creator is unprofitable for most. It’s visible in the math: 3% of YouTubers earn 90% of the platform’s revenue.

What does this mean for the future of the Creator Economy, creators themselves & the hundreds of companies building for them?

Anyone can become a creator.

The Creator Economy has been massively celebrated for its low barriers to entry: Anyone with a phone can become a successful creator. In 2022, Khaby Lame, a Senegalese-born, Italian-based, non-English speaking creator, displaced California’s own Charli Damelio as the #1 TikToker. Quite revealing.

But the lower the barriers to entry, the higher the competition. The size of the arena has grown fast, from 50M creators in 2020 to 200M last year to more than 300M in 2022. With so many creators, the dominance of the algorithmic feed that separates the average from the best is almost inescapable, and with it comes a world with no floor and no ceiling, where the winners take most.

The Fat (Kangaroo's) Tail.

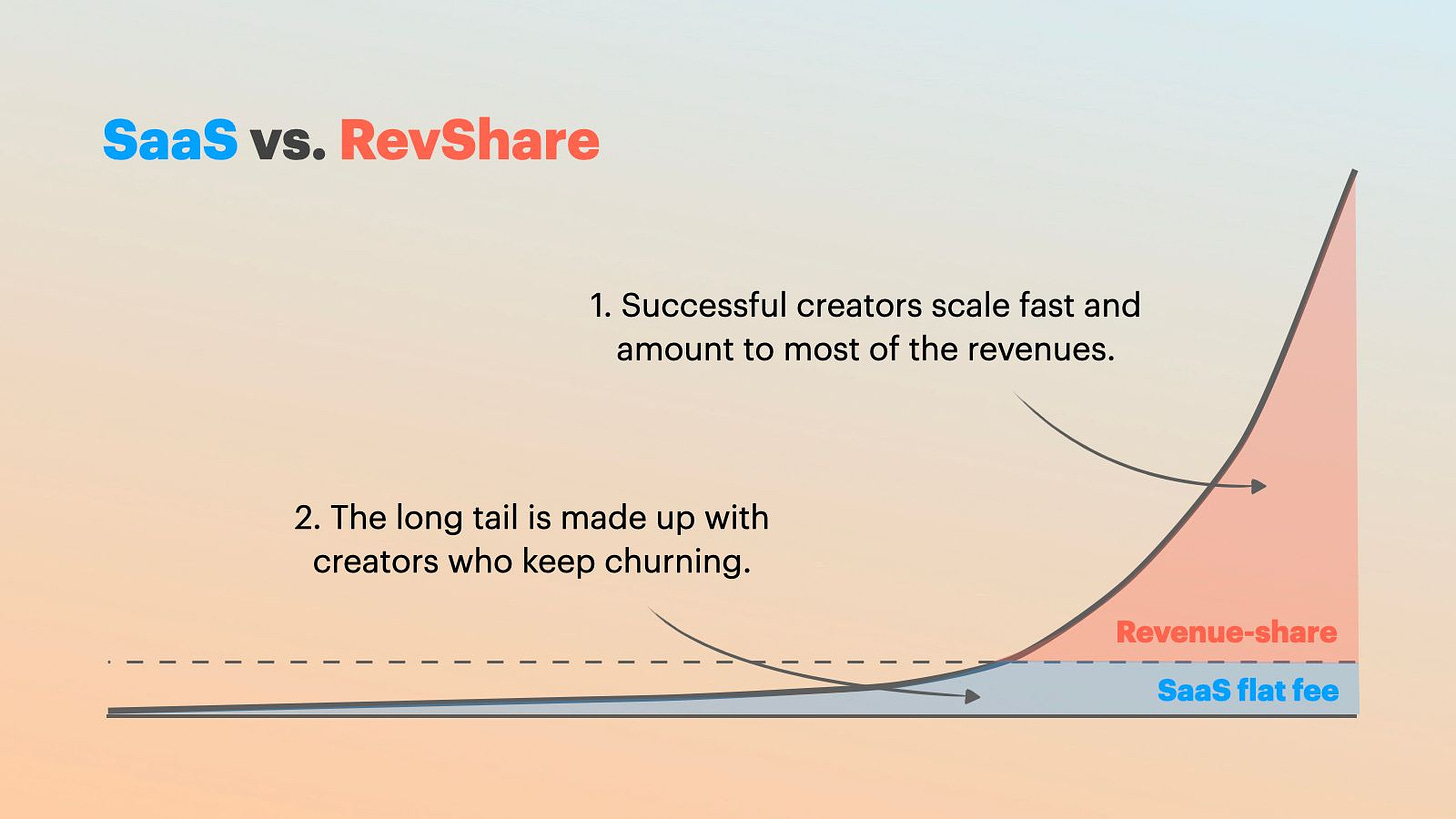

But that’s not all. Not only does the creator economy have a high Gini coefficient, it also has huge mobility. So while it’s true that only 3% of creators are racking 90% of the views on YouTube, the creators making up that successful 3% of YouTubers change all the time. Creators are constantly moving up AND down the tail. Just look at YouTube search results for top creators like David Dobrick, PewDiePie, Emma Chamberlain, and even Charli D’Amelio. They’re all down 60-90% from their ATH.

The tail is fat, but it moves a lot - kind of like a kangaroo. And that’s due to 3 main reasons:

New creators: 25% of Gen-Zers and 30% of 8-12 year olds want to become creators. This trend isn’t going away. The creator world is a red ocean with constant new up-and-coming ambitious talents eating established creators’ lunch. It’s gotten so bad that creators are afraid to take a break, worried about being forgotten by their fans (and the algorithm).

New trends: A rising trend will lift a few creators to the top. Now that everything is trending all at once, most creators are rising and falling with trends. A video game, a vibe shift, a new content style… consumers are less and less faithful, consuming content on TikTok like fashion on Shein. Creators are playing a (literal) platform game where they must jump from trend to trend to stay relevant.

New platforms: Per TikTok exec Alex Zhu, “launching a new platform is like launching a new country: You need to attract people to come to your new land.” New land, new opportunities, new winners. And new formats. Ask The Kardashians how they feel about the shift to short-form videos and an algorithmic feed, and you’ll understand how new platforms could be more threatening to successful creators than new creators or new trends.

The Long Tail doesn’t (yet) exist.

What does it mean? Simply that the Long Tail does not exist economically and that it could indeed end up being nothing more than a theory. When faced with a huge variety of choices, people tend to gravitate more and more toward what they know best. The internet enabled any niche to become a short-term empire with a few creators as temporary princes. That’s why the 1000 True Fans thesis (or inequality, for that matter) cannot be understood as a static concept but only as a dynamic one. In a high-mobility economy like the creator one, the overwhelming majority of creators will ONLY reach 1000 True Fans on their way up to a million or on their way back down to zero. Very few will cruise along with their 1000 True Fans.

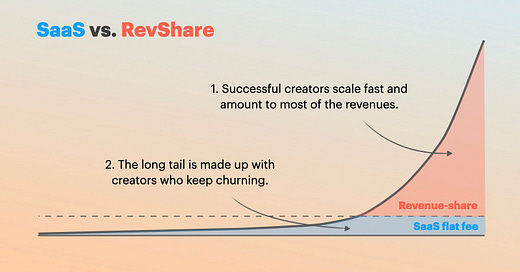

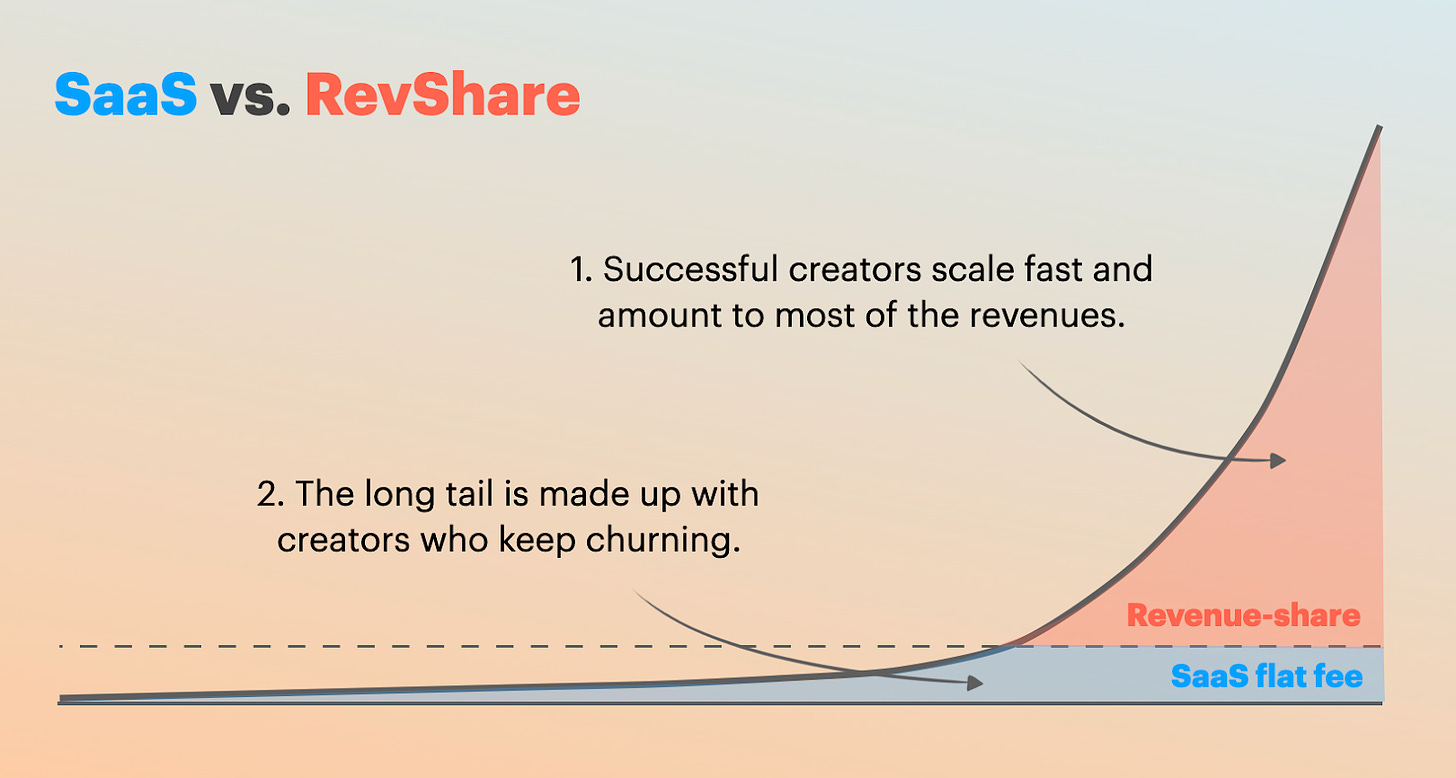

The implications are far-reaching for the Creator Economy in general and companies building for creators in particular. Indeed, the Creator Economy has been copiously referred to as the fastest-growing SMB segment, and lots of founders have been trying to apply the SMB/SaaS playbook to it: 1) Target an SMB segment (long tail), 2) follow your fastest-growing customers & grow pricing/product with them and 3) expand to enterprise-sized customers (fat tail).

Targeting the long tail of creators first would mean facing one of these two problems:

Scale: When they find content-platform fit, creators scale incredibly fast. They go from SMBs to Enterprise in months—not years—and their needs completely change. This makes it very tricky to steadily grow product/pricing with them.

Churn: To stick to the long tail would mean self-selecting for struggling creators whose churn is consequently very high. Then you have to add in their high price sensitivity, making it almost impossible to move up-market.

As a result, the Creator Economy is fat-tail dominated and far more similar to the music industry than the SMB-SaaS market. SMBs don’t scale; artists & creators do. Interestingly, the Music Industry is a decade ahead of the Creator Economy: in the late ‘90s, Napster (and then Spotify) unbundled music from CD/radio, and in the late ‘00s, YouTube unbundled video from TV.

If the music industry is similar to the creator economy, with a decade’s head start, what can we learn from it?

The Music Industry analogy.

Transformed by the internet tsunami, the Music Industry’s revenue halved in less than a decade. Meanwhile, the volume of music published yearly has increased 20x, from one million songs per year in 2000 to over 20 million in 2020. Spotify CEO Daniel Ek estimated that this number would reach 137M in 2025. The Internet has hugely increased competition between artists.

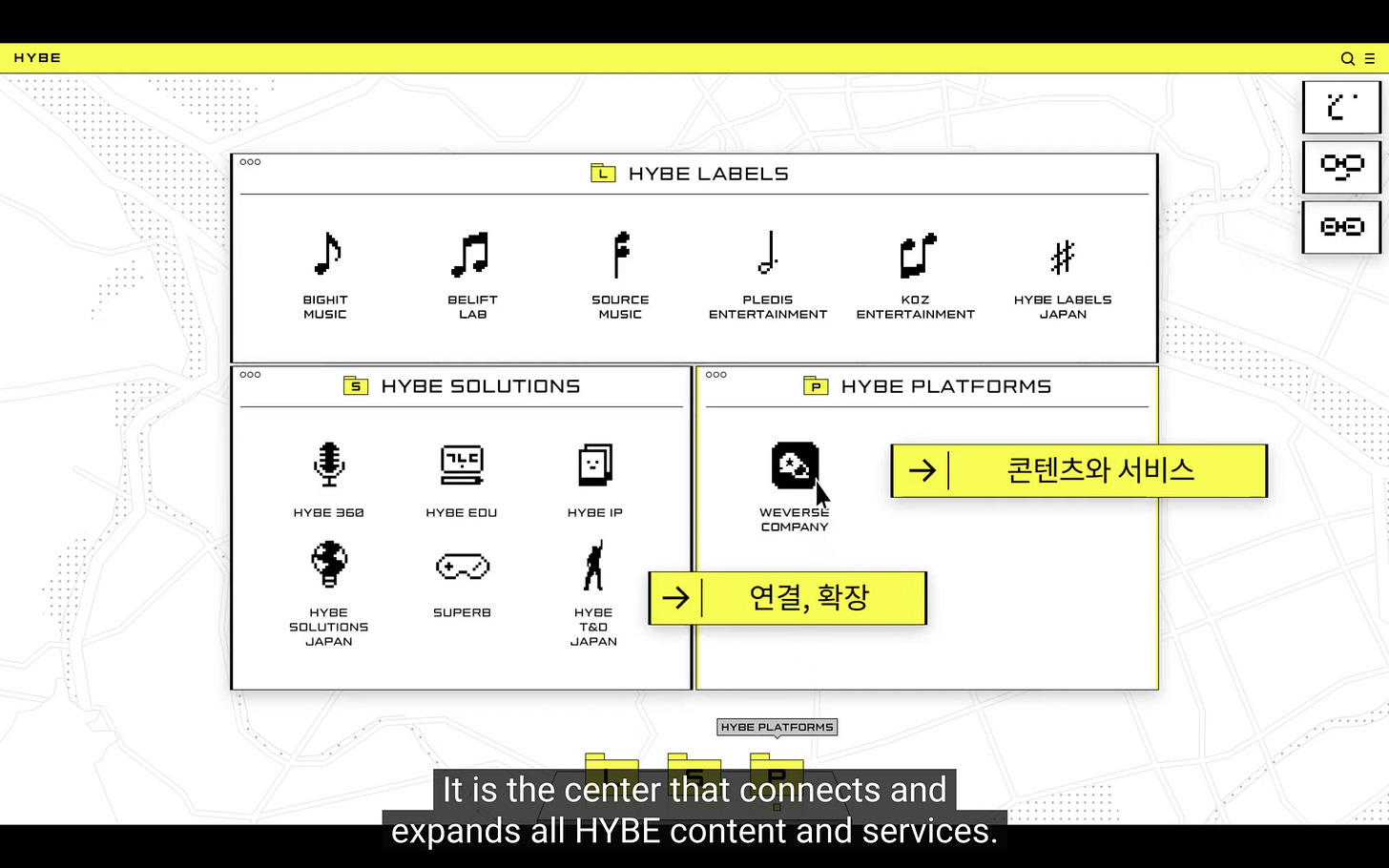

Music output increased dramatically, but what about the size of the tail? On Spotify last year, 1.2% of artists earned 90% of royalties, and over the past 30 years, the share of concert revenue from the top 1% of performers has risen from 26% in 1982 to 60% in 2019. As technology enables artists to increasingly reach a larger and larger audience, a few winners take most. So much so that we’ve witnessed the 1st artists going public with BTS label HYBE IPOing and reaching a 12B market cap last year!

Historically, this superstar-dominated market gave birth to major labels like Universal Music Group, which concentrated the industry and infamously became one of its strongest gatekeepers. With the advent of the internet and the mp3, we have been predicting the death of major labels for almost twenty years.

But did the internet really change the equation?

Why Majors Labels kept thriving.

With music production costs and distribution complexity plummeting, one could think that the major labels would vanish. If anyone can become an artist and find an audience online, why do you need gatekeepers anymore? Well, you don’t. Major labels turned into scale machines. Artists don’t need to ask permission to start their careers, but they still need help scaling them, especially when competition for artists increases 20x in 20 years. And because every artist's dream is to become a superstar, major labels kept thriving.

In addition to being a scaling machine, the majors are also banks that absorb and spread risk over several artists. In fact, of the ~700 artists major labels will sign each year, 9 out of 10 won’t become superstars nor recoup their advances. High risk, high reward.

Let’s take Universal Music Group (UMG) as an example (source):

9 of the top 10 songs on Spotify and 14 of the top 20 are UMG artists.

60% of the top 50 streaming artists on Spotify are UMG artists.

UMG has almost a 40% share of the streaming market overall.

UMG margins went from 13% in 2016 to 18% in 2021.

UMG is worth $35B. Some analysts predict it could reach $100B.

Even Taylor Swift, one of the world's most popular and business-savvy artists, signed a multi-album contract with UMG in 2020! And I could draw the same picture with LiveNation, with its $20B valuation, on the concert side of the industry, but I’ll stop here. The music business is fat-tail dominated, and its winners are concentrated there. Barring a market earthquake, the creator economy is headed this way.

If so, what could a UMG look like in the Creator Economy?

Future Creator Economy winners.

UMG results from the Music Industry’s concentration over nearly a century. The Creator Economy isn’t even a decade old yet and is still quite decentralized. Nevertheless, we’ve already seen some companies emerge as potential category leaders who could ultimately consolidate into a global winner.

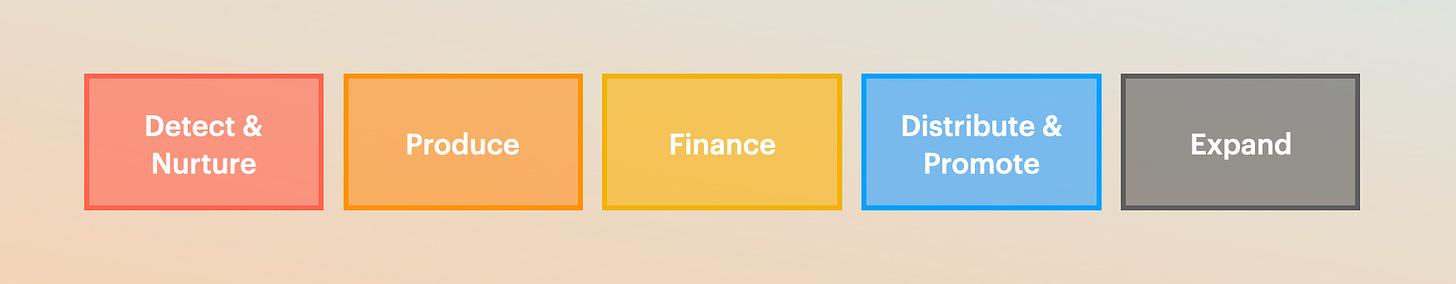

They’re spread across 5 categories:

Detect & Nurture: This is historically the role of a manager. They detect top talent and partner with them in exchange for a commission on deals they land. Legacy talent management companies like CAA, WMD, and UTA have all opened new practices focused on creators. The most interesting new entrant is MrBeast’s management company, Night Media, which is constantly signing the most promising creators and increasingly acting as a business co-founder for creators. Considering that music labels are spending more than $4B annually on A&R, it’s fair to say that we’ve only scratched the surface of this category in the creator world.

Produce: Creators are their own production company, so this is the most decentralized part of the puzzle. Nonetheless, content optimization at scale is increasingly tricky for creators; hence some management companies like Night Media are launching production companies. There’s a huge opportunity for efficient organizations who deeply understand the new formats & trends to build or consolidate internet-native data-driven ‘Own & Operated’ media properties that scale internationally. Jellysmack (disclaimer: I work there) started this way, and Moonbug showed the way with Kids' content; many will soon follow.

Finance: Beyond becoming a producer, it is notoriously hard to finance creators. MCNs, Content Houses—many have already tried their hand at it. The most promising and scalable financing option for video creators today is catalog licensing. Companies like Spotter and Jellysmack offer upfront money on the ad revenues a YouTuber’s back catalog will generate for the next 5 years. Both companies have announced raising hundreds of millions in capital to fund creators.

Distribute & Promote: In the age of Recommendation Media, platforms amount to 90% of a creator’s top-of-funnel. This gave rise to the tech-enabled publisher model, where companies like Jellysmack are abstracting away the complexity of going multi-platform for creators (formats, trends, algorithms, ads, platform relationships, etc). Tech & data can also be leveraged to help creators grow internationally through AI-powered dubbing & collabs with local creators.

Expand: Attention fuels the Creator Lifecycle and enables creators to transform their audience into empires. When MrBeast launches a country-wide burger chain, Popchew enables any creators to do the same. The same is happening to Merch with Fourthwall, DTC brands with Pietra, Communities with Nas, etc. The massive commoditization of the creator business infrastructure is moving OpEx to CapEx for creator organizations and enables them to scale on demand. And with Night Media just announcing a $100M fund with TCG to go in this direction, this is a category with bright days ahead of it.

What do these 5 categories have in common? They’re RevShare-based and fat-tail first: Instead of riding up the long tail with SaaS, they’re sliding down the fat tail with RevShare. They look suspiciously close to the structure of a music label, and something tells me that a similar market consolidation will happen over the course of this decade, as already seems to be the case in the video game industry.

This future Creator Economy giant could seize the lion’s share of a massive market. UMG is a $30B non-tech company in a music streaming market that generated $25B in revenue in 2021. How big is the opportunity for a tech-enabled company in a market where YouTube alone paid creators more than $15B that same year? Quite simply, gigantic.

Will we ever get a creator middle-class?

That's not to say that the creator middle class shouldn’t or can’t ever exist. There are lots of interesting arguments in favor of its development. But in a world with (1) no barriers to entry, (2) no marginal cost of reproduction, (3) non-substitutability where (4) the winners take most, but (5) have (almost) no defensibility, I don’t see the middle-class growing substantially anytime soon. Hence my prediction of a Music Industry like market consolidation in the next 10 years. If the internet is to the 21st century what America was to the 19th century, we might still be in the Gold Rush, and there could still be a long way to go before arriving in the Post-war era.

And remember, almost everything happens at the platform level, which makes it very difficult to implement national policies to mitigate income inequality. As long as Meta, YouTube & TikTok keep fighting the most intense attention war in the history of mankind with god-like algorithmic weapons, there is little hope for the emergence of a vibrant middle class in the Creator Economy.

We are more likely in a barbell situation, with many small creators making $1-2k per month and a few big creators making millions. That said, it’s still the best time to be a content creator in history, and that’s enough for me to celebrate!

🙏

I just published this article on Twitter here, it would mean the world if you could share or just like the post!

Big thanks to Matteo, Zawwar, Paul, Nuseir, Rémi, Quentin, Ben, Ariel, Michael, Chas, Rob, Jim, Tim, Alexa, Niel, Brendan for the feedback & convos—means a lot.